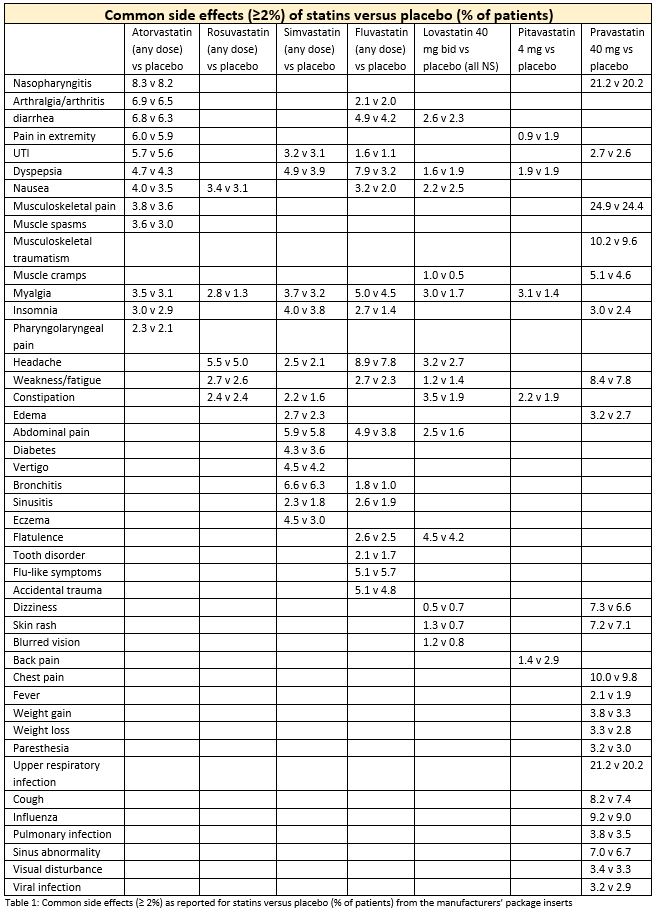

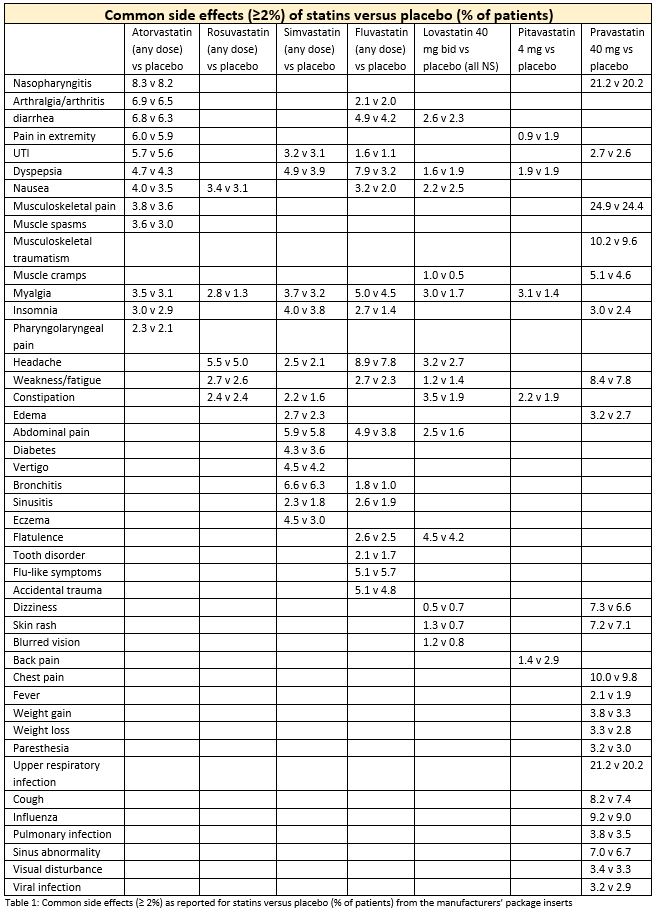

Package inserts for statins available in the United States indicate that rates of common adverse effects that were reported in pre-market trials vary considerably from statin to statin, by dose, and when compared to placebo.1–6 Package inserts do not report on the clinical or statistical significance of these comparative rates.

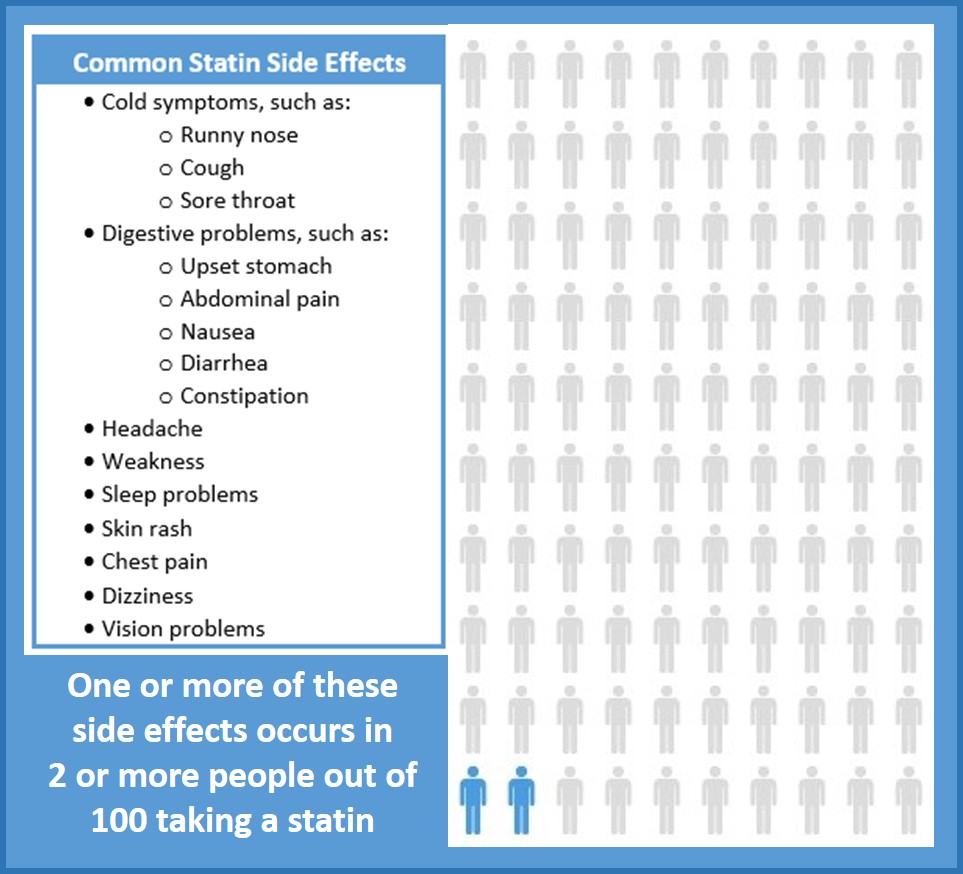

The 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guidelines for Blood Cholesterol Management recommend that physicians and patients discuss statin-associated side effects before initiating therapy to minimize the risk of non-adherence.7 The most frequent statin-associated side effect is myalgia. It is reported in 5% to 29% of patients in clinical trials, registries, and observational studies.8 Many patients who have side effects respond to a statin re-challenge with an alternate statin or revised dosing of the same statin.7

Thompson et al. point out the difficulty of diagnosing statin-associated myalgia (SAMS).9 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of 120 patients with a history of SAMS, 35.8% reported myalgia only when taking simvastatin, 17.5% had no symptoms on simvastatin or placebo, 29.2% reported muscle pain when taking placebo but not when they were taking simvastatin, and 17.5% reported pain when taking both simvastatin and placebo.10

Taylor et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials that evaluated the use of statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (n=34,272).11 In this analysis, adverse event rates were not significantly statistically different between participants treated with statins and controls. In combined data from the five trials that reported event rates for adverse effects, the incidence of myalgia was 7.4% in both treatment and placebo groups.

Parker et al. assessed the effect of atorvastatin 80 mg on 420 statin-naïve healthy patients’ muscle function and performance.12 Objective measures of strength and exercise performance did not differ between those on atorvastatin and controls, but muscle complaints and average creatinine kinase levels differed significantly between the two groups. Average creatine kinase increased 20.8 ± 14.1 U/L (p<0.0001) with atorvastatin suggesting that further study was needed to evaluate prolonged use of high-dose statin therapy on muscle function.

Statins also increase the risk of diabetes in some patients, an effect that may vary by the statin type and dosage used.13 The effect is particularly true for those with metabolic syndrome and on high-dose statin therapy who were at higher baseline risk of diabetes before statins were initiated.14,15 Ridker et al. conducted a randomized double-blind study comparing incidence of cardiovascular endpoints and incident physician-reported diabetes in patients taking rosuvastatin 20 mg (n=8,901) versus placebo (n=8,901).15 Study inclusion criteria included the presence of elevated hs-CRP, which is a marker for insulin resistance. 41% of study participants had metabolic syndrome. The number of people with new-onset diabetes was 0.6% higher in patients taking rosuvastatin compared to placebo. People with diabetes risk factors (metabolic syndrome, impaired fasting blood glucose, BMI >30 kg/m2, or HbA1c >6 percent) on rosuvastatin had a 28% increase in incident diabetes compared to those with risk factors taking placebo. There was no increase compared to placebo in incident diabetes in individuals without risk factors. The authors also calculated the cardiovascular benefit among those on statins. For individuals with diabetes risk factors, 134 vascular events were avoided for every 54 new cases of diabetes.

Case reports have proposed a connection between the use of statins and an increased risk of cognitive problems.16 Cross-sectional studies and randomized controlled studies do not support this relationship.9,17,18 A 2014 Statin Cognitive Safety Task Force analyzed the available evidence to determine if an association exists.19 The authors concluded that, although the quality of existing evidence is low to moderate, it does not a support a connection between statins and adverse cognitive effects. If statin-associated central nervous system effects do exist, they appear to be extremely rare.20 However, in response to reports in its Adverse Events Reporting System, the FDA changed its safety labelling of statins to say: “Memory loss and confusion have been reported with statin use. These reported events were generally not serious and went away once the drug was no longer being taken.”21

References

- Rosuvastatin [package insert]. Wilmington DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceticals, 2010.

- Atorvastatin [package insert]. Dublin Ireland: Pfizer Parke-Davis, 2009.

- Simvastatin [package insert]. Cramlington UK: Merck, Sharpe & Dohne, LTD, 2010.

- Lovastatin [package insert]. Morgantown WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals.

- Fluvastatin [package insert]. East Hanover NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 2012.

- Pitavastatin [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Kowa Pharmaceuticals, 2012.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018.

- Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society consensus panel statement on assessment, aetiology and management. Eur Heart J 2015; 36 (17): 1012-1022.

- Thompson P, Panza G, Zaleski A, Taylor B. Statin-associated side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67 (20): 2395-2410.

- Taylor BA, Lorson L, White CM, Thompson PD. A randomized trial of coenzyme Q10 in patients with confirmed statin myopathy. Atherosclerosis 2015; 238 (2): 329-335.

- Taylor F, Ward K, Moore THM, Burke M, Smith GD. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(1): 1-76.

- Parker BA, Capizzi JA, Grimaldi AS, et al. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle function. Circulation 2013; 127 (1): 96-103.

- Navarese EP, Buffon A, Andreotti F, et al. Meta-analysis of impact of different types and doses of statins on new-onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2013; 111 (8): 1123-1130.

- Waters DD, Ho JE, Boekholdt SM, et al. Cardiovascular event reduction versus new-onset diabetes during atorvastatin therapy: effect of baseline risk factors for diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61 (2): 148-152.

- Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet 2012; 380 (9841): 565-571.

- Wagstaff LR, Mitton MW, Arvik BM, Doraiswamy PM. Statin-associated memory loss: analysis of 60 case reports and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23 (7): 871-880.

- Swiger KJ, Manalac RJ, Blumenthal RS, Blaha MJ, Martin SS. Statins and cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of short- and long-term cognitive effects. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88 (11): 1213-1221.

- Ott BR, Daiello LA, Dahabreh IJ, et al. Do statins impair cognition? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30 (3): 348-358.

- Rojas-Fernandez CH, Goldstein LB, Levey AI, Taylor BA, Bittner V. An assessment by the Statin Cognitive Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol 2014; 8 (3 Suppl): S5-16.

- Martin SS, Sperling LS, Blaha MJ, et al. Clinician-patient risk discussion for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention: importance to implementation of the 2013 ACC/AHA Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65 (13): 1361-1368.

- Statin label changes. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2012; 54 (1386): 21.